Drawing with Confidence, Part 1: Approaching the Blank Page

Stop hesitating and make your mark

Image by Kelly Sikkema

Drawing with Confidence is a free online art course. Develop your drawing skills through playful exercises and thoughtful experimentation. Overcome barriers to self-expression and embrace the joy of mark making.

✅ Part 1 — Key concepts we’ll explore:

Drawing is a tool for understanding and expression, not just representation

There’s no right way to draw — drawing takes many forms

Drawing engages different cognitive processes than verbal thinking

Drawing is Thinking in Action

Drawing is more than a technical skill. It’s a way of thinking visually. When you draw, you’re engaging parts of your brain that understand and process the world differently than verbal thinking. This is why drawing can often reveal and communicate insights and perspectives that words alone cannot capture.

Throughout human history, from prehistoric cave paintings to contemporary digital illustrations, drawing has served as both documentation and exploration. It’s a means to record what we see and to discover what we don’t yet understand. The act of drawing slows our perception, forcing us to notice details we might otherwise overlook and creating space for unexpected connections to emerge.

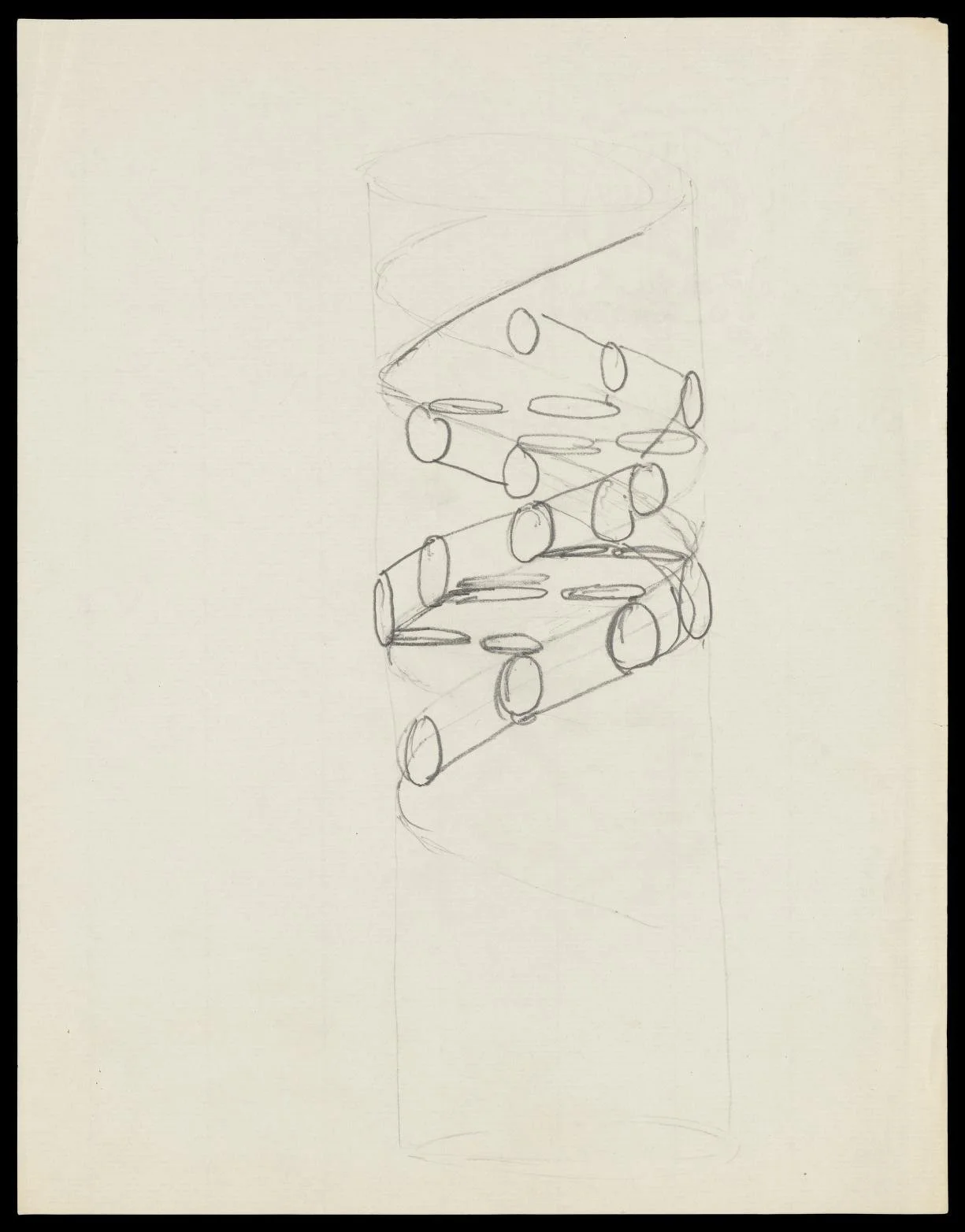

Some of history’s greatest thinkers have used visual thinking to solve problems and develop scientific theories. Leonardo da Vinci used drawing to visualise gravity as a form of acceleration. Francis Crick imagined the twisted ladder of the DNA double helix in a pencil sketch. Marie Tharp sketched detailed maps of the earth’s surface, carefully rendering sonar data into visuals that revolutionised our understanding of our planet’s geology. When we draw, we access a different way of processing information that can lead to unique insights.

Consider this question—When was the last time you drew something to explore or understand, not to create a ‘good’ drawing?

On a new page in your sketchbook, take a moment to jot down some thoughts about a challenge you’re facing or a concept you’d like to understand better. Now, turn to a new page, put your pen to paper, and doodle freely about the same topic for 5 minutes without judgment. Notice the different directions your mind wanders during this visual exploration.

👩🎨 Confidence Boost

That blank page isn’t judging you. It’s just waiting for your unique mark. Remember, your first line doesn’t need to be ‘perfect’. It just needs to exist. Start anywhere on the page—the centre, a corner, with a loose gesture or a deliberate squiggle. If you feel yourself holding back or moving into self-criticism, grab a sheet of paper and scribble to break the tension.

Image by Kelly Sikkema

Exercise: One Hundred Lines

In this exercise, you’ll create 100 unique lines on a single page. You’ll have the opportunity to explore various materials and experiment with pressure, speed, and movement. This will help you build your visual vocabulary and discover your natural drawing tendencies. By opening yourself to new ways of making marks, you’ll push beyond your patterns and discover new possibilities.

Materials

Large sheet of paper (at least A5 /11 × 14 inches)

Various drawing supplies (pencils, pens, markers, etc.)

Timer

Instructions

Divide your paper into approximate sections (they don’t need to be precise)

Set a timer for 30 minutes

Create 100 different lines, exploring as much variety as possible

Use your drawing supplies to experiment with different:

Pressure (light to heavy)

Speed (slow, deliberate to quick, spontaneous)

Tool type and grip

Emotional expression (calm, energetic, hesitant, bold)

Direction and pattern (straight, curved, zigzag, spiral)

Number each line as you go

After completing all 100 lines, circle or star your 5 favourite lines

Reflection

Which lines felt most natural to create?

Which lines were challenging?

Do you notice any patterns in the lines you prefer?

How did your lines change from the beginning to the end of the exercise?

Art in Focus

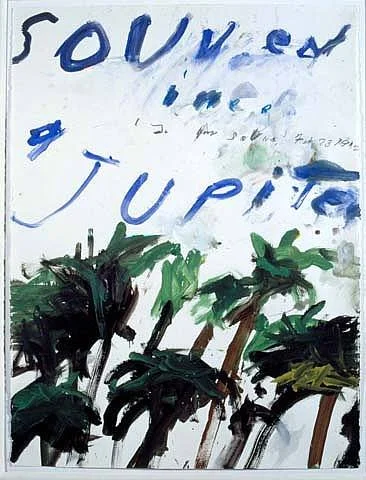

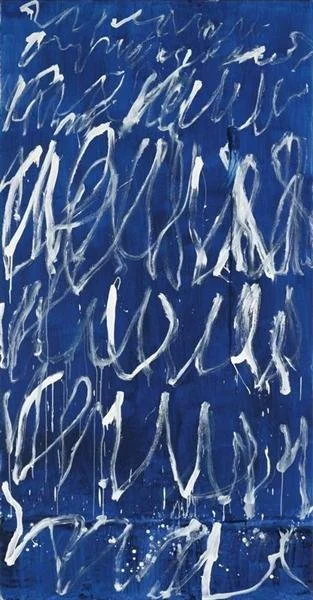

Cy Twombly (1928-2011)

Cy Twombly’s large-scale canvases feature expressive, often scribble-like marks that evoke writing but remain deliberately illegible. His work embraces the raw energy of mark-making and the physical gesture of drawing. These gestural abstractions challenge viewers to reconsider the boundaries between writing and drawing, creating a visual language that is simultaneously intimate and monumental.

Twombly often incorporated references to classical mythology and poetry in his seemingly chaotic compositions, showing how even the most spontaneous-looking marks can carry deep meaning. His lifelong fascination with Mediterranean culture and ancient civilisations provided a rich conceptual foundation that transformed his seemingly simple scrawls into complex meditations on history, literature, and human expression.

‘Each line is now the actual experience with its own innate history. It does not illustrate—it is the sensation of its own realisation’.

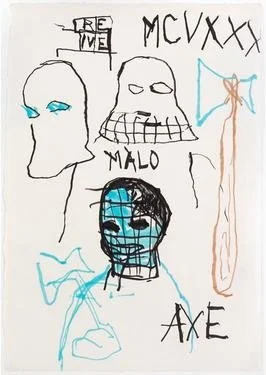

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988)

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (Axe/Rene), 1984. Source

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (Skull), 1981. Source

Rising from the street art scene of 1970s New York, Jean-Michel Basquiat created works that combined drawing, painting, text, and collage elements with seemingly untrained spontaneity. His work embraces a childlike directness while addressing complex themes of identity, racism, and power structures.

Basquiat’s work shows how ‘unskilled’ or deliberate ‘mistakes’ can be powerful artistic choices. His crowns, anatomical diagrams, and scratchings demonstrate an authenticity that transcends traditional notions of good draftsmanship. Despite having no formal art training, Basquiat’s artistic vocabulary drew from his deep knowledge of art history, jazz, and street culture, creating a unique visual language that continues to influence contemporary artists.

Connection to Your Practice

Both Twombly and Basquiat remind us that drawing doesn’t need to be ‘correct’, ‘perfect’, or representational to be powerful. Their work demonstrates how personal mark making of all forms, including scribbles or graffiti-like marks, can communicate emotional and intellectual depth.

Exploration Activity

Look at works by Cy Twombly and Jean-Michel Basquiat. What types of marks do you see repeated? How do these artists use space on the canvas? What emotions do their marks evoke? Create a small drawing inspired by each artist’s approach.

Drawing with Confidence

References

Daigle, C. (2019). Lingering at the threshold between word and image: Cy Twombly – Tate Etc | Tate. [online] Tate. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-13-summer-2008/lingering-threshold-between-word-and-image.

Gharib, M., Roh, C. and Flavio Noca (2022). Leonardo da Vinci’s Visualization of Gravity as a Form of Acceleration. Leonardo, [online] 56(1), pp.21–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/leon_a_02322.

Google Arts & Culture. (2024). Cy Twombly - Google Arts & Culture. [online] Available at: https://artsandculture.google.com/entity/cy-twombly/m052n4b?hl=en.

Google Arts & Culture. (2024). Jean-Michel Basquiat - Google Arts & Culture. [online] Available at: https://artsandculture.google.com/entity/jean-michel-basquiat/m041st?categoryId=artist&hl=en.

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. (n.d.). Sketch of the DNA Double Helix by Francis Crick. [online] Available at: https://www.loc.gov/item/2021669916/.

Marchant, J. (2016). A Journey to the Oldest Cave Paintings in the World. [online] Smithsonian. Available at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/journey-oldest-cave-paintings-world-180957685/.

Metmuseum.org. (2025). Results for ‘Cy Twombly’ - The Metropolitan Museum of Art. [online] Available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search?q=Cy+Twombly&sortBy=Relevance.

North, G.W. (2010). Marie Tharp: The lady who showed us the ocean floors. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C, 35(15-18), pp.881–886. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2010.05.007.

OConnell, S. (2020). Marie Tharp Pioneered Mapping the Bottom of the Ocean 6 Decades Ago – Scientists Are Still Learning About Earth’s Last Frontier. [online] The Conversation. Available at: https://theconversation.com/marie-tharp-pioneered-mapping-the-bottom-of-the-ocean-6-decades-ago-scientists-are-still-learning-about-earths-last-frontier-142451.

The Museum of Modern Art. (2021). Jean-Michel Basquiat | MoMA. [online] Available at: https://www.moma.org/artists/370-jean-michel-basquiat.

Zhou, S.S., Rowchan, K., Mckeown, B., Smallwood, J. and Wammes, J.D. (2024). Drawing behaviour influences ongoing thought patterns and subsequent memory. Consciousness and Cognition, [online] 127, p.103791. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2024.103791.